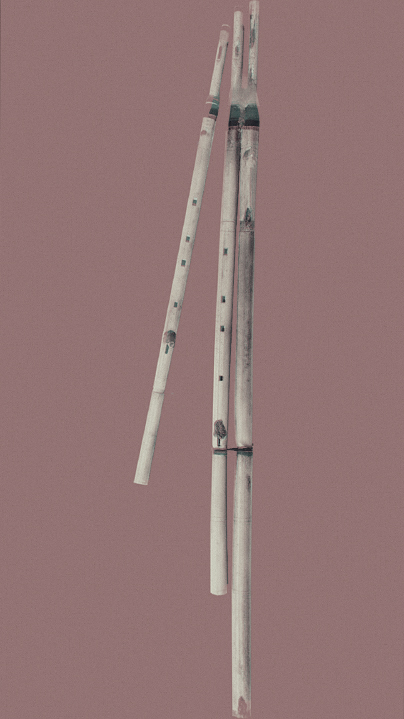

The launeddas consist of three pipes of different lengths that the player supports with his hands. In the upper extremity of the pipes, there is a small piece of cane on which is engraved the reed (cabitzina); the reed vibration produces the sound of the instrument.

The longest drone (tumbu) is without any holes and it produces a single deep and continuous sound. The other two chanters (mancosa and mancosedda) instead have five rectangular holes, four of which are fingered while the last determines the intonation of the instrument when the others are closed.

The launeddas family includes different types of instruments, the cuntzertus, each of which is identified by a specific name (mediana, fioràssiu, puntu ‘e òrganu and many others…).

Executive Technique

The player holds two of the pipes with his left hand (tumbu and mancosa), which are firmly tied together, while holding the highest note chanter (mancosedda) with his right hand.

He brings the three cabitzinas to the mouth (the small pieces of cane on which are engraved the reeds), he closes the lips and he starts to blow, making the reeds vibrate.

Launeddas players use the “circular breathing”.

They accumulate an air reserve in their cheeks, which they use when, breathing in through the nose, they fill the lungs again with air.

Thanks to this special technique it is possible to produce a continuous and uninterrupted sound even for tens of minutes.

Unlike most of the wind instruments, the holes in the two chanters are not plugged with the fingertips but with the phalanges.

These are fingered respectively with the index, middle, ring and little finger of the two hands, while the thumb, resting on the back, supports the instrument.

The History

The Launeddas origins are unknown.

An ancient Nuragic bronze dated XIII – IX century B.C. represents a player of a three pipes instrument: this one could be a progenitor of the instrument that we know today. In ancient times, instruments that have similarities with launeddas were widespread in different parts of the Mediterranean. Various kind of wind instruments with three or two pipes are represented in the frescoes of Egyptian tombs, in the Greek ancient vases and in Roman mosaics.

They date back to the X century A. C. the first sculptural representations of multi-pipes instruments, while the first written sources relating to the presence of launeddas in Sardinia date back to the XIII century. Travel reports, notary deeds and other documents testify to a well-established widespread of this instrument on the island, used by professional musicians, then and now, both as an accompaniment to dance and for the religious processions.

“Launeddas” word – Origins

Since the eighteenth century, many different hypothesis have been proposed.

According to the Abbot Matteo Madau (1787), the term derives from “lion”, because in the past they built the instruments with the tibias of these animals, in his opinion.

In the early twentieth century, the musicologist Giulio Fara and the linguist Pier Enea Guarnerio created a biting controversy on the subject. For the first, the word launeddas would derive from “lau” (laurel), while for the second from “launaxi” (oleander).

To the present day, the most reliable hypothesis about the etymology of the word launeddas is the one proposed by Giulio Paulis.

The linguist Paulis traces the term: from the Latin “ligulella”, diminutive of “ligula” (Italian Language), which would have evolved, over the time, into “liulella”> “liunella”> “liunedda”, up to the current launeddas.

The construction

You need a few simple materials and a wide experience to construct launeddas.

The three pipes and the cabitzinas are made with two different kind of canes. The launeddas makers use the fémina (female) cane for the tumbu and for the cabitzinas where they engrave the reeds. Meanwhile, they use the mascu (male) cane for the chanters.

They use a string (in the past twine of vegetable fiber covered with pitch and, more often, synthetic twine) to tie together tumbu and mancosa and to reinforce the most delicate parts of the instrument. To tune the instrument you need to use beeswax. They apply a small amount of that on the reeds, modifying in this way the vibration frequency.

The instrument makers collect the canes in the days following the full moon of winter and let them mature for at least a year. In their craft laboratories, with the aid of several cutting tools, they make the reeds, they engrave the holes and they assemble the different parts that make up this instrument. An accurate work and a deep knowledge of materials allow them to create perfectly tuned instruments, suitable for the different needs of each player.

The repertoire

The launeddas repertoire includes different types of music: they can play by a solo instrument or a cuncòrdia that means by more than one player at the same time. In some cases, they use launeddas as the accompaniment for singing.

The religious music is an important part of the launeddas repertoire, performed to accompany the Madonna or the saint’s simulacrum during the religious festivals: they carry these simulacrums in procession through the streets of the town, to the sound of the instrument. They play a particular religious sonata inside the church, during the liturgy, at the time of the Elevation of the Host.

However, the most charming and complex part of the launeddas repertoire is the one related to the accompaniment to the dance. With each of the instruments of the launeddas family, the musicians perform the rhythm of the Campidanese dance, a complex music for 3 important aspects: the respect for precise rules, virtuosity and improvisation.

Finally, with the launeddas, they accompany religious songs, like the praise hymns called gòcius, or they accompany profane songs like cantzonis a curba and mutetus.

The launeddas musicians

Learning this ancient instrument requires a long apprenticeship.

Today, as in the past, launeddas music is orally transmitted. Once the trainee musicians learn the circular breathing, they try out with the simplest religious repertoire, usually performed a cuncòrdia or playing along with the accordion, the barrel organ or the cane flutes.

Then they switch to the music that accompanies the dance, the most complex repertoire. For each type of instrument, the Master teaches the trainees a certain number of nodas (musical phrases handed down by tradition). He teaches them different ways to varying the nodas and to linking them with each other.

Launeddas musicians have been music professionals for centuries. After their long apprenticeship, they offer their art for religious celebrations or for performances of dances, occasions in which it cannot miss the important participation of launeddas music.

The launeddas nowadays

In the seventies of the twentieth century, the launeddas went through a period of deep crisis.

Few elderly musicians carried on a centuries-old tradition that was in danger of disappearing.

In the eighties things started to change. The first schools were born: here, masters like Aurelio Porcu and Luigi Lai shared and passed down their knowledge to young people who were starting to approach to this instrument.

In particular, Luigi Lai, still the dean of the launeddas, brought the instruments first to the Folk Revival Festivals and later to the World Music circuits, collaborating with musicians of various backgrounds, like Angelo Branduardi and Maria Carta, from string quartets to players of bagpipes and other instruments from different parts of the world.

Some modern musicians explore the potential of this instrument, experiment new kinds of music and their fusion, carrying out new music projects. Meanwhile, more and more Sardinian people rediscover and start loving the traditional dances to the sound of launeddas.

Like that, they avoided the crisis. Today you can listen to the launeddas, played by musicians of all ages, in many different events: during religious processions, during the local town festivals in the whole island and in International World Music Festivals.